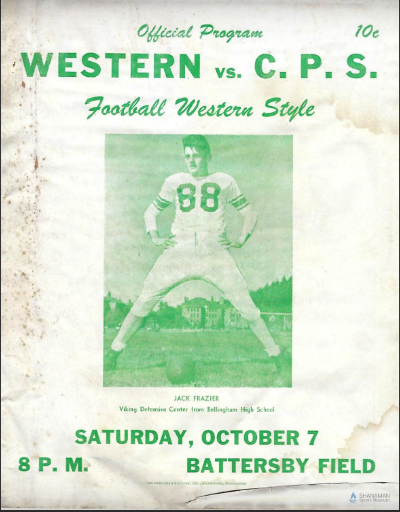

1950 game program vs. University of Puget Sound (then College of Puget Sound). Saturday, Oct. 7, 1950. Game played at Battersby Field. WWU Head Coach: Charles Lappenbusch. External link courtesy of Shanaman Sports Museum.

Game Program vs. UPS (1950)

1950 game program vs. University of Puget Sound (then College of Puget Sound). Saturday, Oct. 7, 1950. Game played at Battersby Field. WWU Head Coach: Charles Lappenbusch. External link courtesy of Shanaman Sports Museum.

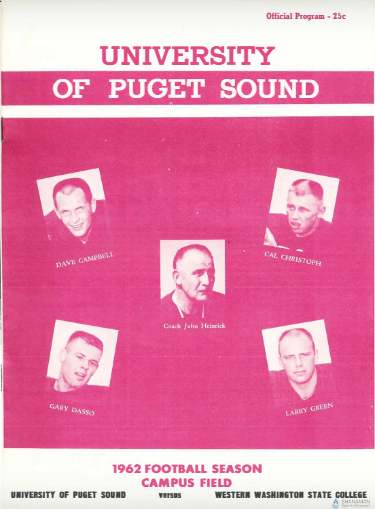

1962 game program vs. University of Puget Sound (then College of Puget Sound). Saturday, Oct. 27, 1962. Game played at Campus Field in Tacoma. WWU Head Coach: Jim Lounsberry. WWU starters included Gary Moore (drafted 17th round by the Green Bay Packers in 1963), Bob Plotts, and Gary Axtell. External link courtesy of Shanaman Sports Museum.

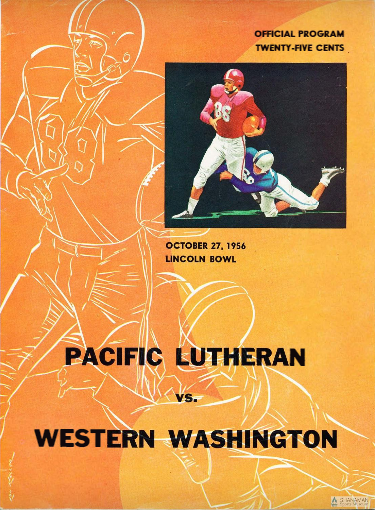

1956 Pacific Lutheran game program. Saturday, Oct. 27, 1956. Game played at the Lincoln Bowl. PLU (then known as the Gladiators) head coach was Marv Harshman. External link courtesy of Shanaman Sports Museum.

Highlights of Kim Nix, Defensive Tackle, #72. 1985-86.

A football program in Washington State commits hara-kiri for the sake of the university’s athletic program.

Officials at Western Washington University reported they are dropping the football program, which began in 1903, in an effort to save other less expensive programs. The Vikings’ move is expected to save the university around $450,000 a year. The cuts were announced Jan. 8.

“I have made this decision with a heavy heart as I am well aware of the profound consequences it has on the student-athletes on the football team, their dedicated and hard-working coaches, and on our passionate supporters on campus, in the community and region, and on our alumni,” said Western President Bruce Shepard in a statement on the program’s cancellation.

Athletics expenditures have grown more rapidly than revenues over recent years, due in part to increased travel costs, field rentals, and a relatively flat growth in gift and donation dollars, according to the university.

Recent budget cuts at the University compounded the program’s financial problems. Among all the options considered, the only way to ensure Western can maintain a strong program of intercollegiate athletics is to eliminate football, according to the university.

Shepard’s release also noted the high cost of running a NCAA Division II football program with the lack of geographically close opponents. Western was one of five Division II schools that sponsor football in the western United States, including the states of Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Montana, and Nevada.

Eileen Coughlin, vice president for student affairs and academic support services, said that Western’s 15 other intercollegiate sports will not be adversely affected and, in fact, will be better protected as the University faces significant budget cuts.

“At Western, the current degree of success in intercollegiate athletics is noteworthy given that programs are stretched very thinly. Ending the football program will allow intercollegiate athletics to meet budget reduction targets, and, most importantly, to protect the quality of the remaining intercollegiate sports,” Coughlin said.

Current football players on scholarship will continue to receive the financial help should they remain at the school, reported the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Those players looking to play elsewhere can transfer and be eligible immediately.

Prior to this announcement, Western had only stopped its football program due to war. The program stopped from 1917 to 1920 for World War I and from 1943 to 1945 for World War II.

Source: What if no one missed college football? | Sports | theworldlink.com

BELLINGHAM, Wash. — The brick-covered quad at Western Washington University is always scrawled with chalked expressions of passion and frustration, joy and happiness.

Baseball is a common theme these days, especially the return of Ken Griffey Jr. to the Seattle Mariners. “Junior, you complete me,” reads one of the notes.

But there are no odes to the loss of the school’s football team.

“Football has just never been a part of the campus culture,” said Western president Bruce Shepard, who started at the school in September after coming from Wisconsin-Green Bay. “Our student body president told our board that one student had complained about the football decision. I have students stopping me in the quad, ‘Bruce, let me shake your hand. I want to thank you for that decision on football.’”

What happens when a school with a century of playing football cuts the sport and only those affected by the decision care? Welcome to WWU, a Division II liberal-arts school overlooking Bellingham Bay where the nearly 14,000 students have had little reaction to the decision made two months ago.

Instead, it’s the players, the coaches scrambling for jobs, and some alumni who are taking issue with the way the school went about cutting a program that started in 1903.

The decision, announced Jan. 8, came without warning or a call for help from alumni or boosters, and from a school president barely four months on the job.

“The president said for some budget reasons they were, instead of making small cuts to all athletic programs, going to drop football completely,” linebacker Caleb Jessup recalled of the meeting where the decision was announced right after students returned from winter break. “Everyone was irate, and upset and crying, and in the flash of an eye changed everyone’s life and changed everyone’s path.”

The decision by Shepard and the WWU administration serves as another example of the challenges small colleges face in trying to balance athletic opportunities and control costs during dire economic times.

Washington state is facing a shortfall of about $8 billion and the initial budget proposed by Gov. Chris Gregoire following her re-election in November called for a 13 percent cut in funding to the state’s universities. The football program at WWU was running a deficit of nearly $500,000 per season.

The school says that cutting football will keep WWU’s other 15 sports stable financially and competitively, even though the school is now out of compliance with Title IX regulations.

“It’s the quantity of opportunities versus the quality of the programs we have,” Shepard said.

But the WWU administration has drawn criticism for the way it went about making its decision and the subsequent cold shoulder it gave to a group of alumni and former players who claim to have raised $1 million in pledges to potentially bring back the program.

Coach Robin Ross believed he was heading into an early morning meeting with Shepard on Jan. 8 regarding recruiting, only to come out knowing that an upcoming trip to the American Football Coaches Assoc-iation conference would now be a job search.

“I would have wanted to be in the conversations and I was not part of that process. I had no idea about the process and how it was conducted,” Ross said. “You would have liked to think that you could have come up with some other alternatives that maybe wouldn’t have resulted in losing the program.”

Documents obtained by the alumni and fan group savewwufootball.com through a Freedom of Information Act request and reviewed by The Associated Press showed that discussions regarding the removal of football began during the 2008 season.

Shepard admits within his first week on campus the idea of cutting football came across his desk. On Dec. 8, an analysis on the impacts for eliminating football began with “Current State fiscal situation makes the elimination of Football a more palatable decision — better public relations.”

Most egregious to those opposed to the decision was the secretive nature of how the decision was made — after Shepard pledged an open, transparent administration — and the lack of communication with boosters and alumni who might have raised funds to help the program.

Shepard says the confidential meetings were necessary and if word had leaked the school was considering cutting football the program was all but dead.

“The other part of the smoke and mirrors that was going on was the comment ‘We didn’t leave any stones unturned,’” said Mark Wolken, president of savewwufootball.com. “To those of us that have been around and watching this the last few years and have a pretty good idea of what’s going on, we’re saying, ‘Now that doesn’t make sense. How can you come to that conclusion?’”

An e-mail from Shepard indicated that as late as Dec. 27 he was not convinced dropping the program was the correct move. Shepard says he had a better idea of the school’s financial situation by Dec. 31, when documents show the process began to eliminate the program.

Also at issue is the school’s initial claim that dropping football would save nearly $500,000 within the first two years. While savings of that amount are projected five years out, the school expects to lose more than $100,000 next year by not having football and Shepard says the amount could be more.

Hampering the efforts of alumni trying to restart the program is the culture at WWU, where students are more apt to participate in intramural sports or explore the area’s abundant outdoor opportunities than to drive 15 minutes across town for a Saturday football game at the city-owned stadium.

“Athletics isn’t a central focus of student life here,” says Erik Lowe, the student body president, who initially attended WWU with the intention of playing football. “… A much smaller percentage of our students have athletics as a key contributor in their decision to come to Western.”

Ultimately the biggest impact from the decision is on players who are scrambling to continue their careers and coaches looking for jobs.

Jessup is one of the lucky ones. A talented linebacker, he’s landed a scholarship at Pittsburg State in Kansas.

Chris Miller, an offensive lineman, is remaining at WWU, but with a skeptical view of the administration.

“How can you trust the administration when they don’t even follow their own policies,” Miller said. “Football was just the first people to get hit with it. I don’t want other people to go through what we went through.”

Source: Former Vikings won’t give up on Western Washington football | The Seattle Times

James Bible, a former running back, offers the thought in a manner as straightforward as a dive play. “I wouldn’t be an attorney and the president of our NAACP chapter if I hadn’t attended Western Washington University and played football.”

James Bible, a former running back, offers the thought in a manner as straightforward as a dive play.

“I wouldn’t be an attorney and the president of our NAACP chapter if I hadn’t attended Western Washington University and played football,” he said. “There’s no question in my mind.”

The oldest of 10 children, raised in a single-parent home, Bible has seen painful glimpses of what he could’ve been if not for Western Washington. He’s seen too many of his siblings go to jail. He’s had to bury one who was murdered. It’s not too dramatic to say the school — especially the Vikings football program — saved his life.

He found himself in Bellingham in the mid-1990s, after roaming from the Idaho and Washington football programs. During his time there, he struggled emotionally after learning his family was wandering around Seattle homeless, but the players and coaches in that football program kept him calm and focused.

“They spent so much time to make sure I carried through with what my objective was,” Bible said.

After reminiscing, he sighed.

“That’s why I’m so disappointed to hear that the football program has been eliminated,” Bible said.

And that’s why, nearly three weeks after the decision, he won’t quit making a big deal of it. Neither will hundreds of players and coaches who came through that program.

They have a Web site, www.savewwufootball.com. They’ve secured pledges to donate more than $500,000 to the athletic department if football is reinstated. And they anticipate the pledges will increase over the next few weeks.

They’ve sent thousands of letters and e-mails to people of influence — politicians, university officials, the board of trustees. They’ve held rallies and have another one planned for Monday in Olympia.

On Jan. 8, Western Washington President Bruce Shepard made the football axing public knowledge, citing the hefty expenses of running the program and cuts in state funding. But this football community cannot stomach that Shepard eliminated a 98-year staple of the university without first seeking help from the alumni. And now he’s saying the move is irreversible? They can’t take it.

Never tell a bunch of old football players it’s over. They won’t listen, especially if there’s no clock winding down to zero.

“We know the odds are against us,” said Jason Stiles, a former quarterback. “We liken it to being down in the fourth quarter. And we’ve never been taught to quit.”

If the concrete on Shepard’s decision was still wet on Jan. 8, it’s dry now — solid, cold and impenetrable. He’s made that clear in meetings with former football players.

Nevertheless, they will keep applying pressure. Why? The program means too much to them.

So in a hopeless time, they’re hopeful.

In a seemingly worthless pursuit, they’re pointing out why football is worthwhile.

“We don’t make it on our own,” Bible said. “We all need help.”

Bible remembers the athletic program posted a bulletin board touting the grade-point averages of its best students. He wanted to be on that board so bad. When he made it, he was so proud.

More than a decade later, he’s a lawyer and the leader of Seattle’s NAACP chapter. “On some levels, I don’t think my story is unique,” Bible said. “A lot of football players, especially African-American football players, found their way there.”

On the day the program was yanked, Bible was talking to a judge who also happened to be a WWU football alum. The judge told him, “If it wasn’t for Western Washington football, I’d be on somebody’s farm milking cows.”

Bible nodded knowingly. Then he told his story. On that day, the lawyer and judge joined the crowd, a bunch of athletes who won’t stop fighting to save a program that saved them.

Some might call their efforts futile. Good thing football taught them to focus.

Jerry Brewer: 206-464-2277 or [email protected]

Source: Western Washing University shuts down its football program after 98 seasons | The Seattle Times

The Western Washington Vikings went 6-5 last season and finished with a victory in the Dixie Rotary Bowl. That left a program begun in 1903 with an all-time record of 383-380-34. WWU Vice President Eileen Coughlin said dropping football will save roughly $485,000 over the next couple of years.

On Western Washington University’s football Web site, next to its 2008 season results, is a notation that can be found accompanying any program across the nation: “There are no upcoming events.”

That advisory took on a haunting poignancy Thursday on the Bellingham campus, where the school announced it was dropping a football program that had existed for 98 seasons.

“It’s almost like a broken heart. I don’t know if I’m ever going to be able to play football again,” said junior receiver Rick Copsey. “I have a queasy stomach. I just kind of feel lost.”

Western Washington administrators cited several factors, including rising operation costs, especially for travel, and sharp state budget cuts that Gov. Christine Gregoire recently put at 13 percent for four-year schools.

Athletic director Lynda Goodrich said the school’s 16-sport program is getting $1.05 million in state aid annually. Vice president Eileen Coughlin said dropping football will save roughly $485,000 over the next couple of years.

Football coach Robin Ross says the school has about 20 scholarship equivalencies divided among about 70 players. Coughlin and Goodrich say the scholarships will be honored, but Copsey said, “I’m sure a good 85 percent will want to transfer out and play football.”

Ross, who played at Washington State from 1974 to 1975, said he got the news in a meeting with Coughlin, Goodrich and school president Bruce Shepard at 8:30 a.m. Thursday.

Western had scheduled five prospects for recruiting visits this weekend, and Ross was ready to arrange with Shepard a time when the recruits could meet with the president.

“In 32 years of coaching, this is the worst day,” Ross said. “I did not have a real good inkling.”

Coughlin said the football program had been losing money in recent years.

Still, Ross had felt the program was on an upswing, saying, “We felt we were one of the programs in the state that actually had some success this year.”

Ross says Western, playing in the Great Northwest Athletic Conference, was featuring fewer scholarships than it had three years ago when he was hired, and that steps were taken to curb expenses next year, such as playing only three games out of state.

“I felt it was all going in the right direction,” Ross said.

The Vikings went 6-5 and finished their season with a victory in the Dixie Rotary Bowl in St. George, Utah, over Colorado School of Mines. That left a program begun in 1903 with an all-time record of 383-380-34.

“I never thought football was in harm’s way,” Copsey said. “Apparently, we were doing a lot worse than any of us thought.”

One of Western’s challenges was being one of the few NCAA Division II programs in the West playing football. The far-flung GNAC had five football-playing members: Central and Western Washington, Humboldt State in Northern California, Western Oregon and Dixie in Utah. They played each other twice a season.

“We hope to proceed with our remaining four institutions,” said Richard Hannan, commissioner of the GNAC. The league is hoping to add Simon Fraser University and University of British Columbia.

“With five [Division II] schools in the West, I would have said their program is as solid as anybody’s,” said Jack Bishop, athletic director at Central Washington. “The thing I guess I worry about in fallout is, who’s next?”

Coughlin said Shepard made the decision two days ago after consultations with Goodrich and Coughlin.

“It was his final call,” Coughlin said of Shepard. “But I have to say: Lynda and I were right there with him.”

Coughlin described the picture as one of interest income from university endowments having dried up with the sour economy, and “athletics was already in a situation where expenditures were greater than revenue. Then along comes the state and says, we’re going to have to cut. We don’t know the full impact of that yet.”

Donations to football, she said, have been running about $80,000 to $85,000 annually, without enough prospect of increase to rescue the sport.

Coughlin and Goodrich lauded Ross for “stellar” leadership, particularly Thursday.

“He asked if he could follow our president today in addressing the athletes,” said Goodrich. “He said, ‘Bruce is going to turn the light off. I want to be able to turn it back on and tell them what other options there are for them, that they can rebound from this.’ “

Ross still has two years left on his contract. He said Western will help try to place players and assistant coaches elsewhere, and that the school will pay for the aides to attend next week’s national coaches convention — a hot spot for job networking — in Nashville.

“I just know some things aren’t ever fair, and this one’s not,” Ross said. “But the reality is, we’ve got to move on and deal with it.”

Bud Withers: 206-464-8281 or [email protected]

Source: Sad day as Western drops football for money reasons | The Seattle Times

The meeting had been scheduled for several weeks. Western Washington football coach Robin Ross wanted to talk to school president Bruce Shepard about recruiting procedures.

Ross had recruits coming to campus this weekend and wanted to know what the president thought the administration’s role should be in these visits.

In other words, when Ross walked into his 8:30 meeting Thursday morning, he was thinking about the future. In fact, he was optimistic about that future.

He had worked hard on budget-cutting issues with the football program. He had cut travel, scheduling five home games for 2009. He had a “money” game scheduled with Eastern Washington.

Ross believed he had the program headed in the right direction. The Vikings, an NCAA Division II team, won six games this season. They won the first bowl game in school history, beating Colorado Mines in the Dixie Rotary Bowl. He felt good about recruiting.

“Then I got into the meeting and I saw it was heading in a different direction,” Ross said by telephone Thursday afternoon.

Instead of talking about the future, Ross learned that his program had no future. He was told by Shepard and athletic director Lynda Goodrich that Western Washington was dropping football. It was eliminating a program that had existed since 1903.

Ross said he felt blindsided.

“It was not something I foresaw,” he said. “It was not something we had discussed. Of course, there’s always budget constraints, and this is kind of a sign of the times. But it was never brought up, how we could raise more money or anything like that.”

Later that morning, Ross met with his staff, then met with his players. He said it was the most painful meeting in his 32 years of coaching.

“That’s where it got real emotional,” he said. “It was tough seeing the expressions on the faces of the guys in that room. That was the toughest part of everything that happened today.

“I explained to them the transfer rules. I told them the school was honoring all of their scholarships until they graduated, but I also told them that this is like a tough loss. You have to bounce back. But it was a shocker for everybody. There’s a lot of disappointment out there. I know there’s a lot of unhappy people.”

People like Jason Stiles, a quarterback at Western in the 1990s.

Stiles still remembers his first day at school, the first meeting of the football team.

“Look around the room,” then-coach Rob Smith told his newest Vikings class. “You might not know anybody in here right now, but the guys in this room are going to become some of your best friends and the friendships you make in this room will be with you for the rest of your life.”

Some 16 years later, Stiles understands precisely what Smith was saying. He says the friendships are part of the ancillary value of playing college football; part of the experience that can’t be measured in dollars and cents, something intangible that, he believes, is necessary at Western.

“I’m furious,” Stiles said. “It’s been a brutal, brutal day of news. Cutting a program that is the cornerstone of the athletic department cannot be an option. It’s unacceptable. Other schools like Western Oregon and Humboldt State have had budget problems, but they’ve found a way to keep the program going.

“I feel terrible for the kids on the team who are having their careers cut short. There are 90 kids in that program, and not all of them are going to find another school to play for.”

Something had to give at Western. The crashing economy and statewide budget cuts are forcing college presidents and athletic directors to make difficult decisions.

Programs are getting re-evaluated. Sports are getting cut. Administrators are being forced into making calls they never thought they’d have to make.

Goodrich called the confluence of economic disasters that forced the university to make this decision “the perfect storm.”

She said endowment cuts were so severe they were “underwater.”

Some sport, or sports, had to go. By eliminating football she could save all the other sports. By dropping football, she could keep Western’s athletic programs afloat in Division II.

“This was the most difficult decision I’ve had to make in my 22 years here,” Goodrich said. “It’s absolutely the toughest day I’ve had to go through, and I’ve been around a long time.”

The hurt in Goodrich’s voice was obvious. She understood the domino effect this would have on the coaches, the players and recruits. She was braced for the anger from alumni and people in the community.

Western’s football history is rich. The school played 797 games. It made five national playoff appearances in the 1990s and made it to the NAIA Division II championship game in 1996.

Former Viking Michael Koenen is the punter in Atlanta. Dane Looker, who later transferred to Washington, is a receiver in St. Louis. And linebacker Shane Simmons was an undrafted free agent with Oakland.

“It’s a really sad day,” said Central Washington coach Blaine Bennett, whose football team is the state’s only remaining Division II program. “It’s always hard when a school loses football. I was at Chico State right before they dropped football, and it’s tough.

“We’ve lost a great, great rival. With the Battle in Seattle at Qwest Field every year we’d developed something really special for the kids at both schools. I feel really bad for the kids and the coaching staff. I’m hoping we can find places for some of the players on their team.”

As costs escalate and revenue drops, other schools are making similar difficult decisions. In Western’s Great Northwest Athletic Conference, Humboldt State and Western Oregon are facing financial problems. There only are four football-playing schools left in the league.

“I’m concerned about the trickle-down effect this is going to have for the rest of the conference,” Stiles said. “And I hate the fact that they made a permanent decision based on temporary economic conditions that ultimately are going to get better.

“And I don’t like the fact that we weren’t notified. Nobody reached out to us to let us respond. To not give the alumni and family a chance to respond is beyond me.”

Ross, who has been an assistant coach at five Division I schools and in the NFL with Oakland, is 54 and says he believes he has 10 to 12 more years of coaching left in him. He also has two years left on his contract with Western.

But for Ross the grief he felt Thursday was for his assistants and his players.

“We play a good brand of football here, and I think people were starting to realize that,” he said. “I just don’t think it’s a good answer to the [budget] problem to eliminate possible options for kids. It’s a sad day, but we all have to move on.”

Steve Kelley: 206-464-2176 or [email protected]. More columns at www.seattletimes.com/columnists

WWU vs Central Washington University Wildcats from Ellensburg, WA on November 16, 1991.